“In India our religions will never take root. The ancient wisdom of the human race will not be displaced by what happened in Galilee. On the contrary, Indian philosophy streams back to Europe, and will produce a fundamental change in our knowledge and thought.”

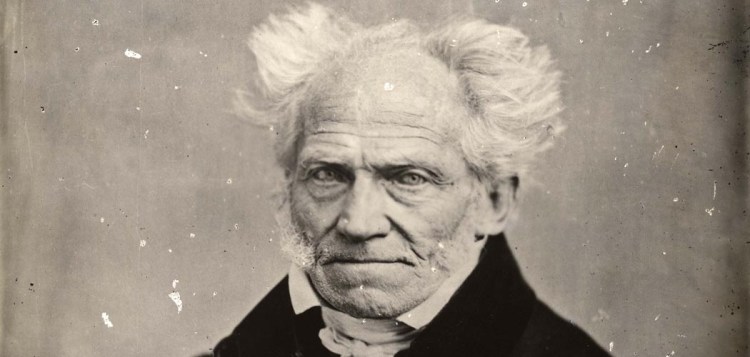

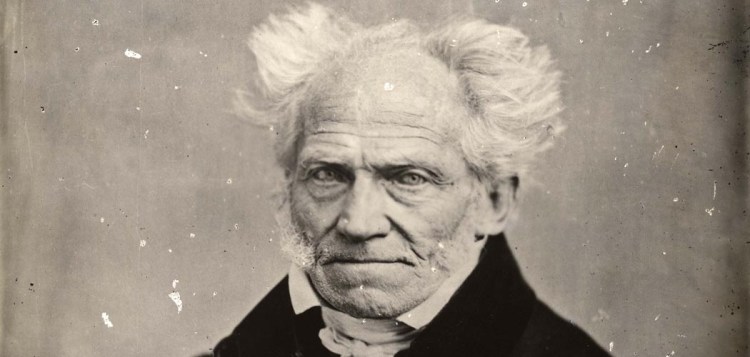

– Arthur Schopenhauer

Full Book (PDF): The World as Will and Representation – Volume I – Volume II

Full Book (PDF): On the Basis of Morality

Schopenhauer’s Thought

A key focus of Schopenhauer was his investigation of individual motivation. Before Schopenhauer, Hegel had popularized the concept of Zeitgeist, the idea that society consisted of a collective consciousness that moved in a distinct direction, dictating the actions of its members. Schopenhauer, a reader of both Kant and Hegel, criticized their logical optimism and the belief that individual morality could be determined by society and reason. Schopenhauer believed that humans were motivated by only their own basic desires, or Wille zum Leben (“Will to Live”), which directed all of mankind.

For Schopenhauer, human desire was futile, illogical, directionless, and, by extension, so was all human action in the world. Einstein paraphrased his views as follows: “Man can indeed do what he wants, but he cannot will what he wants.” In this sense, he adhered to the Fichtean principle of idealism: “The world is for a subject.” This idealism so presented, immediately commits it to an ethical attitude, unlike the purely epistemological concerns of Descartes and Berkeley. To Schopenhauer, the Will is a blind force that controls not only the actions of individual, intelligent agents, but ultimately all observable phenomena—an evil to be terminated via mankind’s duties: asceticism and chastity. He is credited with one of the most famous opening lines of philosophy: “The world is my representation.” Will, for Schopenhauer, is what Kant called the “thing-in-itself”. Friedrich Nietzsche was greatly influenced by this idea of Will, although he eventually rejected it.

For Schopenhauer, human desiring, “willing”, and craving cause suffering or pain. A temporary way to escape this pain is through aesthetic contemplation (a method comparable to Zapffe’s “Sublimation“). Aesthetic contemplation allows one to escape this pain—albeit temporarily—because it stops one perceiving the world as mere presentation. Instead, one no longer perceives the world as an object of perception (therefore as subject to the Principle of Sufficient Grounds; time, space and causality) from which one is separated; rather one becomes one with that perception: “one can thus no longer separate the perceiver from the perception” (The World as Will and Representation, section 34). From this immersion with the world one no longer views oneself as an individual who suffers in the world due to one’s individual will but, rather, becomes a “subject of cognition” to a perception that is “Pure, will-less, timeless” (section 34) where the essence, “ideas”, of the world are shown. Art is the practical consequence of this brief aesthetic contemplation as it attempts to depict one’s immersion with the world, thus tries to depict the essence/pure ideas of the world. Music, for Schopenhauer, was the purest form of art because it was the one that depicted the will itself without it appearing as subject to the Principle of Sufficient Grounds, therefore as an individual object. According to Daniel Albright, “Schopenhauer thought that music was the only art that did not merely copy ideas, but actually embodied the will itself”.

He deemed music a timeless, universal language comprehended everywhere, that can imbue global enthusiasm, if in possession of a significant melody.

Will as Noumenon

Schopenhauer accepted Kant’s double-aspect of the universe—the phenomenal (world of experience) and the noumenal (the true world, independent of experience). Some commentators suggest that Schopenhauer claimed that the noumenon, or thing-in-itself, was the basis for Schopenhauer’s concept of the will. Other commentators suggest that Schopenhauer considered will to be only a subset of the “thing-in-itself” class, namely that which we can most directly experience.

Schopenhauer’s identification of the Kantian noumenon (i.e., the actually existing entity) with what he termed “will” deserves some explanation. The noumenon was what Kant called the Ding an sich (the Thing in Itself), the reality that is the foundation of our sensory and mental representations of an external world. In Kantian terms, those sensory and mental representations are mere phenomena. Schopenhauer departed from Kant in his description of the relationship between the phenomenon and the noumenon. According to Kant, things-in-themselves ground the phenomenal representations in our minds; Schopenhauer, on the other hand, believed that phenomena and noumena are two different sides of the same coin. Noumena do not cause phenomena, but rather phenomena are simply the way by which our minds perceive the noumena, according to the principle of sufficient reason.

Schopenhauer’s second major departure from Kant’s epistemology concerns the body. Kant’s philosophy was formulated as a response to the radical philosophical skepticism of David Hume, who claimed that causality could not be observed empirically. Schopenhauer begins by arguing that Kant’s demarcation between external objects, knowable only as phenomena, and the Thing in Itself of noumenon, contains a significant omission. There is, in fact, one physical object we know more intimately than we know any object of sense perception: our own body.

We know our human bodies have boundaries and occupy space, the same way other objects known only through our named senses do. Though we seldom think of our body as a physical object, we know even before reflection that it shares some of an object’s properties. We understand that a watermelon cannot successfully occupy the same space as an oncoming truck; we know that if we tried to repeat the experiment with our own body, we would obtain similar results—we know this even if we do not understand the physics involved.

We know that our consciousness inhabits a physical body, similar to other physical objects only known as phenomena. Yet our consciousness is not commensurate with our body. Most of us possess the power of voluntary motion. We usually are not aware of the breathing of our lungs or the beating of our heart unless somehow our attention is called to them. Our ability to control either is limited. Our kidneys command our attention on their schedule rather than one we choose. Few of us have any idea what our liver is doing right now, though this organ is as needful as lungs, heart, or kidneys. The conscious mind is the servant, not the master, of these and other organs. These organs have an agenda the conscious mind did not choose, and over which it has limited power.

When Schopenhauer identifies the noumenon with the desires, needs, and impulses in us that we name “will”, what he is saying is that we participate in the reality of an otherwise unachievable world outside the mind through will. We cannot prove that our mental picture of an outside world corresponds with a reality by reasoning; through will, we know—without thinking—that the world can stimulate us. We suffer fear, or desire: these states arise involuntarily; they arise prior to reflection; they arise even when the conscious mind would prefer to hold them at bay. The rational mind is, for Schopenhauer, a leaf borne along in a stream of pre-reflective and largely unconscious emotion. That stream is will, and through will, if not through logic, we can participate in the underlying reality beyond mere phenomena. It is for this reason that Schopenhauer identifies the noumenon with what we call our will.

In his criticism of Kant, Schopenhauer claimed that sensation and understanding are separate and distinct abilities. Yet, for Kant, an object is known through each of them. Kant wrote: “[T]here are two stems of human knowledge … namely, sensibility and understanding, objects being given by the former [sensibility] and thought by the latter [understanding].” Schopenhauer disagreed. He asserted that mere sense impressions, not objects, are given by sensibility. According to Schopenhauer, objects are intuitively perceived by understanding and are discursively thought by reason (Kant had claimed that (1) the understanding thinks objects through concepts and that (2) reason seeks the unconditioned or ultimate answer to “why?”). Schopenhauer said that Kant’s mistake regarding perception resulted in all of the obscurity and difficult confusion that is exhibited in the Transcendental Analytic section of his critique.

Lastly, Schopenhauer departed from Kant in how he interpreted the Platonic ideas. In The World as Will and Representation Schopenhauer explicitly stated:

…Kant used the word [Idea] wrongly as well as illegitimately, although Plato had already taken possession of it, and used it most appropriately.

Instead Schopenhauer relied upon the Neoplatonist interpretation of the biographer Diogenes Laërtius from Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers. In reference to Plato’s Ideas, Schopenhauer quotes Laërtius verbatim in an explanatory footnote.

Diogenes Laërtius (III, 12): Plato teaches that the Ideas exist in nature, so to speak, as patterns or prototypes, and that the remainder of things only resemble them, and exist as their copies.

Moral Theory

Schopenhauer’s moral theory proposed that only compassion can drive moral acts. According to Schopenhauer, compassion alone is the good of the object of the acts, that is, they cannot be inspired by either the prospect of personal utility or the feeling of duty. Mankind can also be guided by egoism and malice. Egotistic acts are those guided by self-interest, desire for pleasure or happiness. Schopenhauer believed most of our deeds belong to this class. Acts of malice are different from egotistic acts. As in the case of acts of compassion, these do not target personal utility. Their aim is to cause damage to others, independently of personal gains. He believed, like Swami Vivekananda in the unity of all with one-self and also believed that ego is the origin of pain and conflicts, that reduction of ego frames the moral principles.

Even though Schopenhauer ended his treatise on the freedom of human will with the postulate of everyone’s responsibility for their character and, consequently, acts—the responsibility following from one’s being the Will as noumenon (from which also all the characters and creations come)—he considered his views incompatible with theism, on grounds of fatalism and, more generally, responsibility for evil. In Schopenhauer’s philosophy the dogmas of Christianity lose their significance, and the “Last Judgment” is no longer preceded by anything—”The world is itself the Last Judgment on it.” Whereas God, if he existed, would be evil.

He named a force within man that he felt took invariable precedence over reason: the Will to Live or Will to Life (Wille zum Leben), defined as an inherent drive within human beings, and indeed all creatures, to stay alive; a force that inveigles us into reproducing.

Schopenhauer refused to conceive of love as either trifling or accidental, but rather understood it as an immensely powerful force that lay unseen within man’s psyche and dramatically shaped the world:

The ultimate aim of all love affairs … is more important than all other aims in man’s life; and therefore it is quite worthy of the profound seriousness with which everyone pursues it. What is decided by it is nothing less than the composition of the next generation.

Influence of Eastern Thought

Schopenhauer read the Latin translation of the ancient Hindu texts, The Upanishads, which French writer Anquetil du Perron had translated from the Persian translation of Prince Dara Shikoh entitled Sirre-Akbar (“The Great Secret”). He was so impressed by their philosophy that he called them “the production of the highest human wisdom”, and believed they contained superhuman concepts. The Upanishads was a great source of inspiration to Schopenhauer. Writing about them, he said:

It is the most satisfying and elevating reading (with the exception of the original text) which is possible in the world; it has been the solace of my life and will be the solace of my death.

It is well known that the book Oupnekhat (Upanishad) always lay open on his table, and he invariably studied it before sleeping at night. He called the opening up of Sanskrit literature “the greatest gift of our century”, and predicted that the philosophy and knowledge of the Upanishads would become the cherished faith of the West.

Schopenhauer was first introduced to the 1802 Latin Upanishad translation through Friedrich Majer. They met during the winter of 1813–1814 in Weimar at the home of Schopenhauer’s mother according to the biographer Safranski. Majer was a follower of Herder, and an early Indologist. Schopenhauer did not begin a serious study of the Indic texts, however, until the summer of 1814. Sansfranski maintains that between 1815 and 1817, Schopenhauer had another important cross-pollination with Indian thought in Dresden. This was through his neighbor of two years, Karl Christian Friedrich Krause. Krause was then a minor and rather unorthodox philosopher who attempted to mix his own ideas with that of ancient Indian wisdom. Krause had also mastered Sanskrit, unlike Schopenhauer, and the two developed a professional relationship. It was from Krause that Schopenhauer learned meditation and received the closest thing to expert advice concerning Indian thought.

Most noticeable, in the case of Schopenhauer’s work, was the significance of the Chandogya Upanishad, whose Mahavakya, Tat Tvam Asi is mentioned throughout The World as Will and Representation.

Schopenhauer noted a correspondence between his doctrines and the Four Noble Truths of Buddhism. Similarities centered on the principles that life involves suffering, that suffering is caused by desire (taṇhā), and that the extinction of desire leads to liberation. Thus three of the four “truths of the Buddha” correspond to Schopenhauer’s doctrine of the will. In Buddhism, however, while greed and lust are always unskillful, desire is ethically variable – it can be skillful, unskillful, or neutral.

For Schopenhauer, Will had ontological primacy over the intellect; in other words, desire is understood to be prior to thought. Schopenhauer felt this was similar to notions of puruṣārtha or goals of life in Vedānta Hinduism.

In Schopenhauer’s philosophy, denial of the will is attained by either:

- personal experience of an extremely great suffering that leads to loss of the will to live; or

- knowledge of the essential nature of life in the world through observation of the suffering of other people.

However, Buddhist nirvāṇa is not equivalent to the condition that Schopenhauer described as denial of the will. Nirvāṇa is not the extinguishing of the person as some Western scholars have thought, but only the “extinguishing” (the literal meaning of nirvana) of the flames of greed, hatred, and delusion that assail a person’s character. Occult historian Joscelyn Godwin (1945– ) stated, “It was Buddhism that inspired the philosophy of Arthur Schopenhauer, and, through him, attracted Richard Wagner. This Orientalism reflected the struggle of the German Romantics, in the words of Leon Poliakov, to “free themselves from Judeo-Christian fetters”. In contradistinction to Godwin’s claim that Buddhism inspired Schopenhauer, the philosopher himself made the following statement in his discussion of religions:

If I wished to take the results of my philosophy as the standard of truth, I should have to concede to Buddhism pre-eminence over the others. In any case, it must be a pleasure to me to see my doctrine in such close agreement with a religion that the majority of men on earth hold as their own, for this numbers far more followers than any other. And this agreement must be yet the more pleasing to me, inasmuch as in my philosophizing I have certainly not been under its influence. For up till 1818, when my work appeared, there was to be found in Europe only a very few accounts of Buddhism.

Buddhist philosopher Nishitani Keiji, however, sought to distance Buddhism from Schopenhauer. While Schopenhauer’s philosophy may sound rather mystical in such a summary, his methodology was resolutely empirical, rather than speculative or transcendental:

Philosophy … is a science, and as such has no articles of faith; accordingly, in it nothing can be assumed as existing except what is either positively given empirically, or demonstrated through indubitable conclusions.

Also note:

This actual world of what is knowable, in which we are and which is in us, remains both the material and the limit of our consideration.

The argument that Buddhism affected Schopenhauer’s philosophy more than any other Dharmic faith loses more credence when viewed in light of the fact that Schopenhauer did not begin a serious study of Buddhism until after the publication of The World as Will and Representation in 1818. Scholars have started to revise earlier views about Schopenhauer’s discovery of Buddhism. Proof of early interest and influence, however, appears in Schopenhauer’s 1815/16 notes (transcribed and translated by Urs App) about Buddhism. They are included in a recent case study that traces Schopenhauer’s interest in Buddhism and documents its influence. Other scholarly work questions how similar Schopenhauer’s philosophy actually is to Buddhism.

Schopenhauer said he was influenced by the Upanishads, Immanuel Kant and Plato. References to Eastern philosophy and religion appear frequently in his writing. As noted above, he appreciated the teachings of the Buddha and even called himself a Buddhist. He said that his philosophy could not have been conceived before these teachings were available.

Concerning the Upanishads and Vedas, he writes in The World as Will and Representation:

If the reader has also received the benefit of the Vedas, the access to which by means of the Upanishads is in my eyes the greatest privilege which this still young century (1818) may claim before all previous centuries, if then the reader, I say, has received his initiation in primeval Indian wisdom, and received it with an open heart, he will be prepared in the very best way for hearing what I have to tell him. It will not sound to him strange, as to many others, much less disagreeable; for I might, if it did not sound conceited, contend that every one of the detached statements which constitute the Upanishads, may be deduced as a necessary result from the fundamental thoughts which I have to enunciate, though those deductions themselves are by no means to be found there.

Among Schopenhauer’s other influences were: Shakespeare, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, John Locke, Thomas Reid, Baruch Spinoza, Matthias Claudius, George Berkeley, David Hume, and René Descartes.

Schopenhauer’s Influence

Schopenhauer has had a massive influence upon later thinkers, though more so in the arts (especially literature and music) and psychology than in philosophy. His popularity peaked in the early twentieth century, especially during the Modernist era, and waned somewhat thereafter. Nevertheless, a number of recent publications have reinterpreted and modernised the study of Schopenhauer. His theory is also being explored by some modern philosophers as a precursor to evolutionary theory and modern evolutionary psychology.

Russian writer and philosopher Leo Tolstoy was greatly influenced by Schopenhauer. After reading Schopenhauer’s The World as Will and Representation, Tolstoy gradually became converted to the ascetic morality upheld in that work as the proper spiritual path for the upper classes: “Do you know what this summer has meant for me? Constant raptures over Schopenhauer and a whole series of spiritual delights which I’ve never experienced before. … no student has ever studied so much on his course, and learned so much, as I have this summer”

Richard Wagner, writing in his autobiography, remembered his first impression that Schopenhauer left on him (when he read The World as Will and Representation):

Schopenhauer’s book was never completely out of my mind, and by the following summer I had studied it from cover to cover four times. It had a radical influence on my whole life.

Wagner also commented on that “serious mood, which was trying to find ecstatic expression” created by Schopenhauer inspired the conception of Tristan und Isolde.

Friedrich Nietzsche owed the awakening of his philosophical interest to reading The World as Will and Representation and admitted that he was one of the few philosophers that he respected, dedicating to him his essay Schopenhauer als Erzieher one of his Untimely Meditations.

Jorge Luis Borges remarked that the reason he had never attempted to write a systematic account of his world view, despite his penchant for philosophy and metaphysics in particular, was because Schopenhauer had already written it for him.

As a teenager, Ludwig Wittgenstein adopted Schopenhauer’s epistemological idealism. However, after his study of the philosophy of mathematics, he rejected epistemological idealism for Gottlob Frege’s conceptual realism. In later years, Wittgenstein was highly dismissive of Schopenhauer, describing him as an ultimately shallow thinker: “Schopenhauer has quite a crude mind… where real depth starts, his comes to an end.”

The philosopher Gilbert Ryle read Schopenhauer’s works as a student, but later largely forgot them, only to unwittingly recycle ideas from Schopenhauer in his The Concept of Mind (1949).

Further Study

Arthur Schopenhauer (SEP)

Arthur Schopenhauer (IEP)

Schopenhauer’s Works (Project Gutenberg)

Schopenhauer’s Works (Wikisource)